At their heart, movie novelizations are meant to be somewhat disposable; pieces of marking as a way for studios to broaden their advertising reach, and for publishers to make a quick buck with a release that is sure to grab reader’s attention. So it should come as no surprise that most novelizations come and go with little fanfare on their way to become obscure footnotes in literary history. Some novels though manage to break through and find a large audience, or the films that they are adapting become such mega blockbusters that this success alone gives their associated novelizations a wave to ride on for years and sometimes decades. We just wrote about how the adaptation of Scarface managed to break sales records months before the release of Brian De Palma’s celebrated film back in 1983, and it seems like books like the Star Wars and Alien franchise adaptations will always have volumes in print. But, this rare super success that some novelizations attain has led to a very interesting phenomenon in the genre which is when an adaptation receives a follow up in print regardless of any plans for actual film sequels.

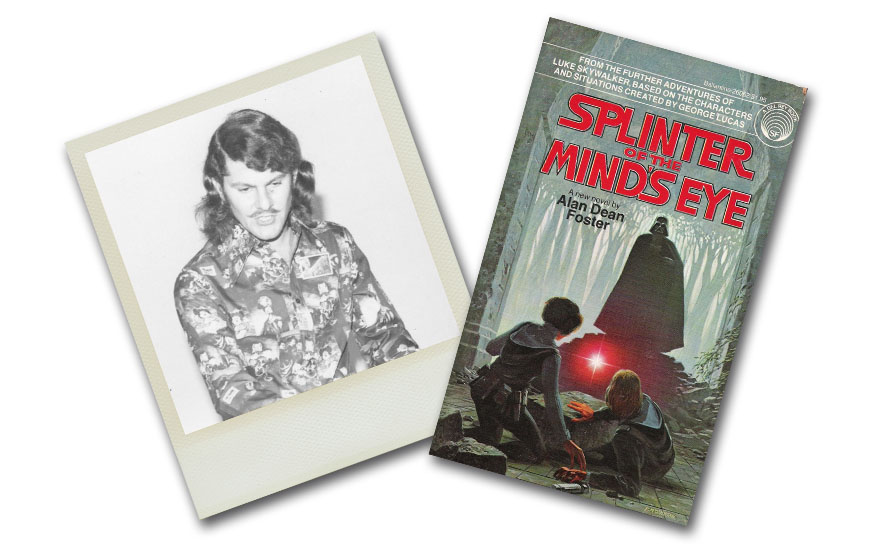

In 1977 Star Wars broke box office and records and found millions of fans across the country. Before the film was a smashing records though, George Lucas had a plan start buzz and marketing for the movie almost a year before it would eventually be released in theaters. In the summer of 1976 he “wrote” a novelization of his script that was published by Ballantine Books in November of that year. Featuring production artwork by Ralph McQuarrie on the cover, the book was perceived as having been the source material on which the new film was based. Legend has it that Lucas, seeing the success his friend Francis Ford Coppola was having after adapting the best selling book The Godfather to film, decided it would add a sense of quality to his film project if the public thought that the movie was based on a book. In the years since its publication it has come out that Lucas hired famed science fiction writer Alan Dean Foster to ghostwrite the novel based on Lucas’ script. As a part of that deal, Foster was also given the go ahead to draft a sequel to the film, a story which Foster titled Splinter of the Mind’s Eye which told of the further adventures of Luke Skywalker & Princess Leia as they again battled the evil Darth Vader. The story was published by the Del Rey arm of Ballantine as a novel in February of 1978. Though Lucas eventually decided to go in a different direction when he ramped up production on his follow up film, The Empire Strikes Back, the book remained as the seed that would eventually grow into the bountiful expanded universe of Star Wars novels.

In 1977 Star Wars broke box office and records and found millions of fans across the country. Before the film was a smashing records though, George Lucas had a plan start buzz and marketing for the movie almost a year before it would eventually be released in theaters. In the summer of 1976 he “wrote” a novelization of his script that was published by Ballantine Books in November of that year. Featuring production artwork by Ralph McQuarrie on the cover, the book was perceived as having been the source material on which the new film was based. Legend has it that Lucas, seeing the success his friend Francis Ford Coppola was having after adapting the best selling book The Godfather to film, decided it would add a sense of quality to his film project if the public thought that the movie was based on a book. In the years since its publication it has come out that Lucas hired famed science fiction writer Alan Dean Foster to ghostwrite the novel based on Lucas’ script. As a part of that deal, Foster was also given the go ahead to draft a sequel to the film, a story which Foster titled Splinter of the Mind’s Eye which told of the further adventures of Luke Skywalker & Princess Leia as they again battled the evil Darth Vader. The story was published by the Del Rey arm of Ballantine as a novel in February of 1978. Though Lucas eventually decided to go in a different direction when he ramped up production on his follow up film, The Empire Strikes Back, the book remained as the seed that would eventually grow into the bountiful expanded universe of Star Wars novels.

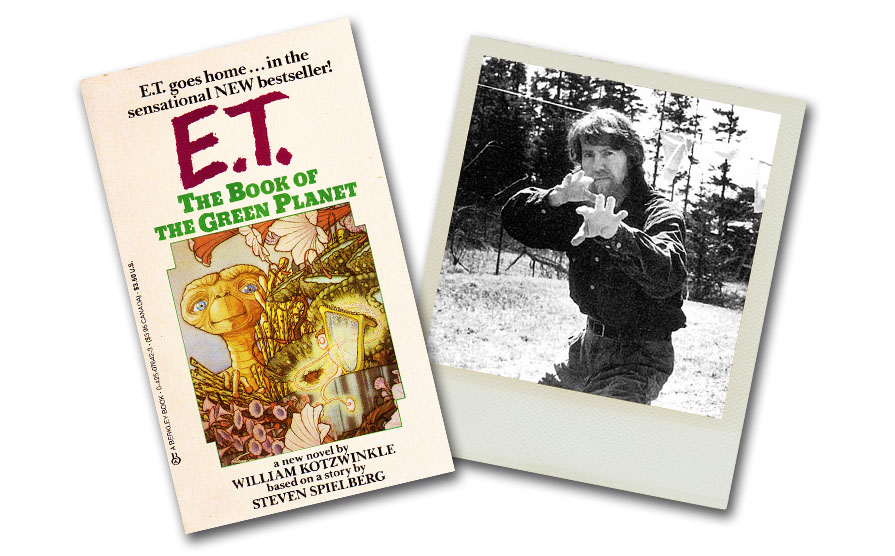

Similar in vein to Foster’s tale is the journey that Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra Terrestrial took from script to novelization, and eventually to a psedu-sequel. Released in conjunction with the film in 1982, William Kozwinkle’s novelization became a surprise break-out hit. At a time when the VHS rental industry was still in its infancy and most households didn’t own a VCR, novelizations were a go-to for anyone who wanted to revisit films that had already left theater screens. With the monumental success of the film, Kozwinkle’s novel was an affordable way for kids and adults that were kids at heart all over the country to relive the adventures of E.T. and Elliott. The the novel was also potentially popular as a novelty considering that Kozwinkle chose a very odd voice to narrate the story, that of E.T. himself. Though it ended up providing some new and odd insight into characters that we don’t get in the film and eluded to some odd scenarios between E.T. and Elliott’s mother, the book was enough of a hit that Spielberg gave the go-ahead to Kozwinkle to write a sequel novel that would potentially serve as the basis of a cinematic sequel as well. Published in 1985, Kozwinkle’s sequel, E.T. the Book of the Green Planet, picked up with the story years later after the extra terrestrial had returned to his home planet of Brodo Asogi.

Unburdened by adhering to a script, Kotzwinkle decided to let loose in the sequel revealing that E.T. is not merely an alien from another world, but a traveler from outside of our universe/dimension. In an odd turn, unlike in the novelization of the film where E.T. is portrayed very distant and monk-like, Kozwinkle decided to mold the character more into the image we get in the actual film for this sequel book. Kozwinkle illustrates him as playfully ignorant and continuously spouting incorrect English to his friends as if he had learned to master the language during his layover on Earth. He’s also described as being depressed, having left his newfound friends behind on Earth, never to see them again. Considering that he’s described as being almost 10 million years-old in the first novelization, this seems a bit awkward and weird implying that he’s lived throughout the millennia having never formed any other bonds of friendship. Was his experience with Elliott that profound, and if so, how boring was the rest of his existence? Besides, for a being of that age who travels through out dimensions and across galaxies with ease, isn’t it a bit naïve to assume one would never see their friends again? Al in all the book is a very weird, yet interesting follow-up to a beloved classic film. The novel left itself open for a third story that sadly has yet to materialize.

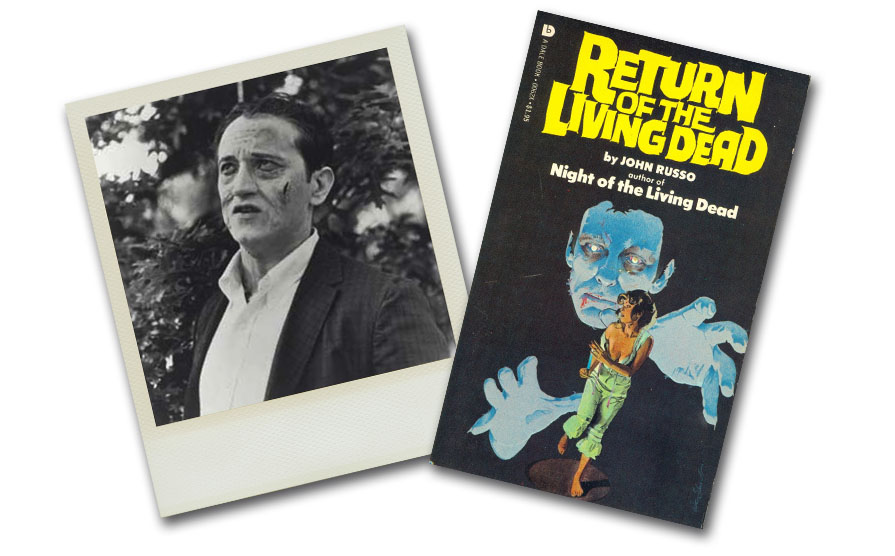

Before audiences were being taken to galaxies far, far away and tearing up at the bond between a boy and his best alien friend, John Russo was having a hell of a time scaring the pants off of us with the world of the Living Dead. A few years after collaborating on a script with George Romero that became the film Night of the Living Dead, Russo decided to try his hand at adapting the story into a novelization. At the time this was potentially an attempt to try and siphon off some of the profits from the film’s popularity. Because of a mistake during the editing and processing of the prints of the film when it was retitled during it’s initial distribution, the standard copyright notice was left off and the film was thrust into the public domain making it near impossible for Romero or Russo to profit off of the distribution of the film during re-releases or later on home video. We’re not sure what prompted them to stop working together after that first Living Dead film, but the duo split the rights to the original story and in 1978 while George Romero was set to release Dawn of the Dead, his follow up to the 1968 film, Russo decided to release his own follow up as a sequel to his 1974 novelization which he titled Return of the Living Dead (published by Dale.)

The book, which draws heavily on the first novelization (even going so far as to reuse much of the supporting text segments), is a nihilistic gore-fest that follows a small town being torn apart by a new plague of zombies after a horrific school bus crash. Russo had wanted to make a film of his novelization sequel, but a deal wouldn’t be cemented until almost six years later when Dan O’Bannon worked on a new draft of the story which changed much of the core story and tone. In 1985 the new script was produced into a feature film, and then in a weird twist, John Russo ended up adapting the film into yet another novelization also titled Return of the Living Dead. So not only did Russo write a sequel novel to his original novelization, but also a sequel novelization.