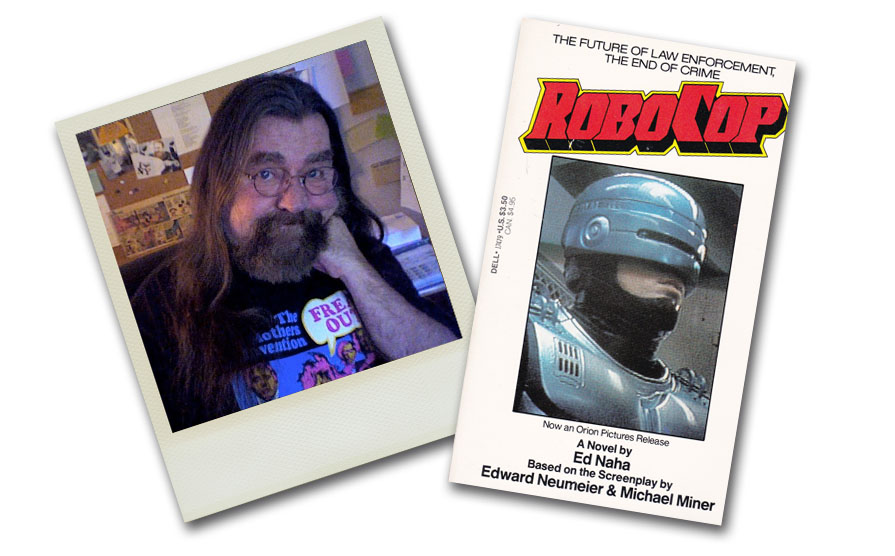

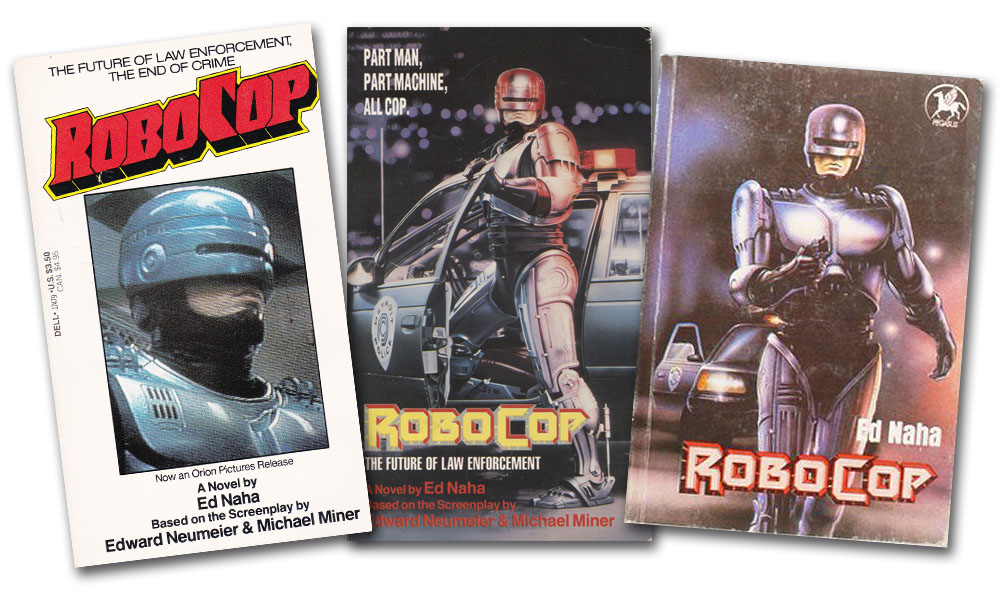

In the realm of movie novelizations, there are a handful of books that just seem, well, unlikely. Whether it’s an adaptation of a film that just does not seem like it would make for a good book (like Three Amigos), or one that would have an uphill battle of trying to recreate the visceral, sometimes mind-blowing, imagery that is on the screen. In the late 80s Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, writers Edward Neumeier & Michael Miner, and an amazing cast and crew created a film that has yet to be matched in terms of maniacal mix of audacity, violence, beauty, and satire. Robocop burst into theaters and changed the landscape of filmmaking for decades to come. Simultaneously, the novelization bust onto bookshelves and, well, didn’t make near the amount of impact that the film did, but it is still one heck of an interesting take on the material. When it comes to novelizations, our favorites are always the books that feel a bit meatier when it comes to page count. So many of the thinner books we come across are strict adaptations of movie scripts with little to no new material. In fact, they tend to omit some scenes from the actual film version of the story. Before we read it, Robocop had always made us wonder where it fell on the spectrum of faithful to creative novelizations because it clocks in at a very tight 189 pages. After reading it, we realized that author Ed Naha is not only a skilled writer armed with an efficient sense for brevity when the story needs it, but he also managed to leave in (or add) details from the script that never made it to the screen.

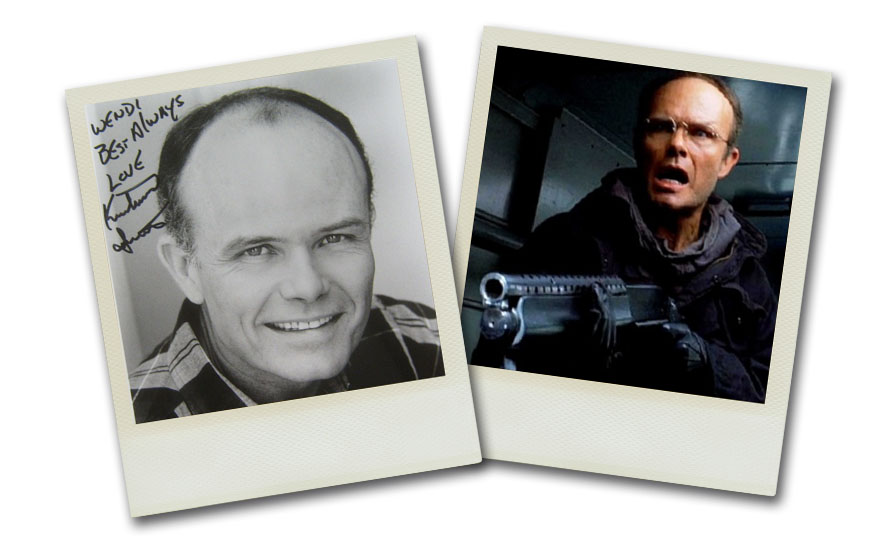

First and foremost, even though it clearly states on the cover that Ed Naha adapted the novel from the Edward Neumeier & Michael Miner script, some of the text belies the fact that Naha must have seen a cut of the film based on descriptions of the characters that are dead-on for the actors that portrayed them. The illustration of Clarence Boddicker’s appearance matches Kurtwood Smith’s extremely close, and we’ve even scanned through the Neumeier/Miner script which doesn’t describe the character as accurately. Maybe casting had already begun and the writing assignment came with actor headshots? We find this bit interesting because writers tend to only receive scripts to work from and it’s rare that they have a window into the production beyond early artwork and design concepts. Playing devil’s advocate though, maybe this is just our brains filling in all the little details of the final film as we read. This is one of the bits of strange phenomena we struggle with while reading novelizations because the films are so ingrained in our minds that it’s hard not to see the film playing out as we read. This is also why, when we’re describing scenes that are in the book but not the film, we can’t help but refer to them as “deleted scenes”. Even though we have no actual memory of ever seeing these bit and pieces that were excised from the film, we can so vividly picture them in our heads. Speaking of which, there are a fair number of deleted scenes in this book (and in the script) that flesh out the characters and situations in the story a bit more.

One that struck us takes place as the book opens on a quiet moment at home with Murphy and his family. This is the morning/day before he starts his new shift in Old Detroit and it gets into a little bit more about his past and his family. In the flick we only ever see Murphy’s wife (Jan) and son (Jimmy) in flashbacks or hallucinations, but in the book we get a couple of scenes with them before and after Murphy is murdered by the Boddicker gang. In this early scene Murphy is thinking about his new assignment and it reminds him about the death of his father and how he was murdered by a stray bullet while standing at the picture window of their home. Naha doesn’t dwell on this, but it underlines a tone in the film when it comes to death and violence. As his father is dying, Alex notes that he seems almost amused, and just manages to say “Sumabitch…” before dying. This is echoed in the sequence where Murphy is slaughtered by the gang later on, where he finally seems to understand what his dad’s final thoughts were probably like.

In the second deleted sequence with Murphy’s family we visit Jan & Jimmy as they’re packing up the house in preparation for leaving on a shuttle to a colony on the moon. There’s just a beat here, of somber emotion that is great for filling in the gaps with Alex’s family life, but we understand why it was cut from the film as it would have totally thrown off the wacky, ultra-crazed tone of the narrative. In both of these sequences there are also a ton more references to the story-within-a-story character of “TJ Lazer”. Lazer makes it into the film in a couple bits where Murphy practices twirling his gun so that his kid will think he’s cool (just like TJ Lazer.) The book ends up mentioning Lazer about fifteen additional times, even going so far as to describe the show so that it sounds like a futuristic version of T.J. Hooker, complete with an overweight, past-his-prime actor like William Shatner. When Murphy finally transitions into Robocop, we get a short scene with his son Jimmy watching him on TV and then falling in love with him as his new hero (replacing good ‘ol TJ Lazer.)

There’s also a new sequence early on in the book involving a handful of Old Detroit cops on a night when everything just seems to go horribly wrong. Two patrol cars are lured into an empty parking lot and then ambushed by Boddicker’s gang. The book gets pretty descriptive with the murders, which are even more over the top than Murphy’s murder in the final film (if one can believe it.) This sequence underlines a subplot in the film that we think tends to get lost in the shuffle. The whole idea that Old Detroit is as rough and violent as it is, not just because of the dystopian future, but because it was made that way specifically by the character Dick Jones. Jones, who needs his ED 209 project to have legs enough (pun fully intended) to go to full production so that they can land some lucrative military contacts, basically calls for an open season on Old Detroit and hires Boddicker and his gang to make the place a war zone. In the film this sub plot is there, but because of the amped up, uber-violent, uber-sarcastic tone to the narrative, it tends to get lost our my opinion. This opening scene of the police massacre plays to this subplot though. By massacring the police Boddicker’s men are sending a message, so much so that they even (and quite literally) paint the death-count of each murdered cop on their body armor with spray paint. The book further underlines this later during a chase sequence where Murphy and Lewis pursue Boddicker’s gang to their hideout. During the gunfight in the van, Naha has Boddicker thinking about how much he hates situations where he has to kill because he wasn’t specifically paid to do it. Again, it gets to this idea that every evil event that Boddicker and company perpetrate on Old Detroit is specifically ordered by Dick Jones. Again, it’s not that this doesn’t make it into the film, it’s just more clear when you read the story as opposed to experience the stylized version in the film.

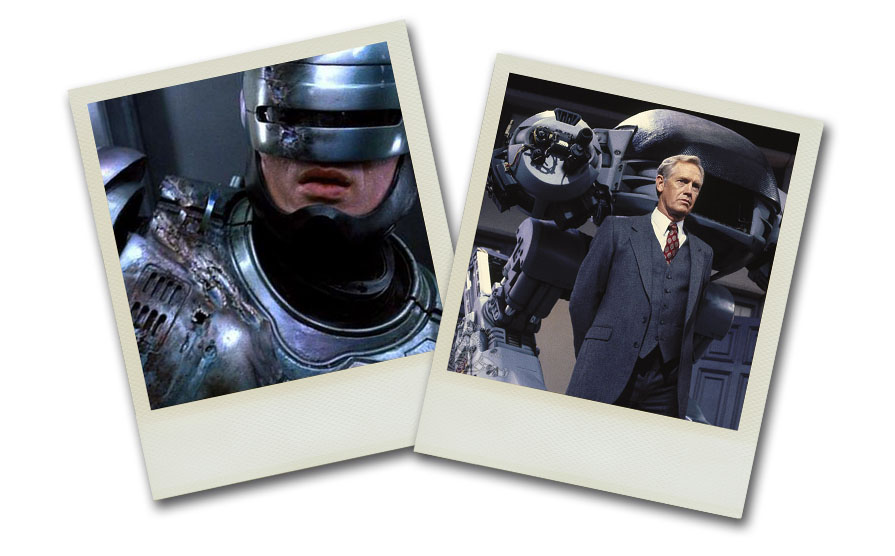

There are also a lot of interesting small differences between the book and the film, a lot of which revolve around Murphy after he’s murdered and reconstructed into Robocop. Most of these are welcome peeks into Murphy/Robocop’s inner monologue, stuff that’s hard to do on film without clunky voiceover. For instance, there’s a who section where we witness Murphy’s slaughter by the Boddicker gang from his perspective which is vastly different than how we experience it in the film. In the movie we’re forced to act as a witness, one that has to watch the brutality from the point of view of the killers. In the book, we’re inside Murphy’s head as he slips past shock and unbearable pain into a more detached, transcendental state of consciousness. The reader is almost treated as if we’re his essence starting an out of body experience as the character finds the whole situation almost comical. It’s during these moments, and in the time when he’s lying waiting for the medical evacuation team when Naha uses a framing device to showcase Murphy’s consciousness flickering in and out. Murphy checks himself on things, like his ability to remember what a helicopter is as it touches down near his body, or what it feels like to be strapped down to a gurney. These checks are revisited after he wakes as Robocop, but as the machine he explains his observations with a self awareness that he has been programmed to know these things. Slowly, as Murphy’s soul and brain overtake the machine, these metal checks revert back to how he felt as he was dying. It’s a fascinating narrative device that we’re probably not explaining as well as it comes across in Naha’s novelization.

Some of the other little touches that we really enjoy include the fact that Robocop has the ability to test a person’s blood alcohol level just by his proximity to their breathing. So, during the new year’s eve party, when he is about to be introduced to the police force and the one drunk female scientist comes over to Murphy and kisses his visor, he’s able to make a notation about just how inebriated she is based on her breath! We also thought it was interesting that in the book Robocop isn’t as immune to damage as he appears to be in the film. Though it’s cool to see Murphy kicking ass and walking through hails of bullets and fire, it was always a little weird to us that he seemed invulnerable up until he tried to arrest Dick Jones, thus initiating directive 4 in his programming. We never really understood what exactly it was about directive 4 that basically revokes Robocop’s ability to deflect bullets. He’s shot up a bunch of times early in the film only to have all the bullets bounce off, but after attempting to arrest Jones all bullets seem to penetrate his armor. In the book this comes across very different. For one, he’s only really bulletproof to small arms fire, so later when the police are brought in to take him down they’re using armor piercing rounds. But Robocop’s vulnerability is also addressed in the gas station scene where he’s apprehending Emil. When the gas station explodes it ends up charring Robocop’s armor, so much so that it remains this way throughout the rest of the book. In fact, in the sequence right after that incident, when Murphy/Robocop storms into the police records archive he’s still smoldering in that room. Though the book lacks a lot of the satire that ends up on screen, Naha does have some fun with product placement in the gas station seq. He mentions that during the explosion the “S” in the Shell station sign goes flying off the building leaving only a flashing neon “HELL” over the situation.

Robocop as a character is also a lot more expressive in the book than in the film. He has a more developed sense of humor, makes jokes at times, and has very human mannerisms like shrugging his shoulders at criminals that don’t comply or giving a two finger salute to bystanders after he’s arrested someone. Though it’s fun to imagine a lighter-hearted Robocop, and we understand why Naha inserted this sort of humanizing body language into the book, it feels very out of place with the character (that we know and love) and dulls the switch-over from him being an OCP product back in to a sentient, more human Murphy. Also, for all the work Naha put into the inner-awareness framing device, it’s sort of undermined by a more human Robocop. Similarly, in this vein, Naha also has Robocop make some weird observations as he’s accessing situations. In the scene where he goes into City Hall to rescue the Mayor from the deranged city councilman, there’s a bit where he’s analyzing the walls of the rooms to try and find a way into the situation without using his gun. While scanning the wall of the room where the hostages are he notates that the structure was rebuilt in the 80s using overpriced, subpar building materials. How would Robocop know that the materials were overpriced? Maybe he has access to all of the city’s records up to and including invoices for contract construction work done over the past century?

One of the last differences we want to bring up involves a sequence where Boddicker is sent in to kill Morton (by Dick Jones.) First off, Naha changes one of the most classic Boddicker lines in the film (and in the script), the one he says when he first comes into Morton’s condo. He utters the two words that set the tone for this scene, “Bitches Leave.” In the book, when Boddicker comes in Naha has him say, “Okay sluts. Take a hike.” Not nearly as efficiently evil, and no where near as iconic. We’re not sure why he decided to change this because it’s clearly in the script. Not only does he change this, but Naha also weirdly adds a softer side to Clarence in this scene with the addition of Morton’s cat. The cat comes walking into the room while Morton is begging for his life and Boddicker reaches down and pets it. This pisses off Morton, who considers the cat a traitor, and then as Boddicker is leaving, while Morton is fumbling for the grenade, Clarence picks up the cat and takes it with him. On the one hand, this is kind of weirdly cold to have a killer acting nice to an animal in the middle of murdering someone, but it’s also conflicting a bit with his character that typically comes off as if he has no compassion what-so-ever. A sense of humor, yes, but compassion, no.

Naha adds some fun little pop culture references in the book that we wanted to point out. Early on he has Murphy quote from the 1941 Wolfman film with this foreboding line, “Even a man who is pure of heart and says his prayers by night…”. It foreshadows Murphy’s transformation nicely. Of course there’s also the William Shatner/T.J. Hooker bits we mentioned above, but there’s another actor reference that really got a chuckle out of us while reading. After Robocop becomes a fugitive and Dick Jones is settling back into his warzone of an office he flips on the television to a news story about the death of Sylvester Stallone. Stallone was having his brain transplanted into a clone body and died during the operation.

Lastly, if all of these differences weren’t interesting enough, after the climactic final battle at the abandoned factory, Robocop ends up finding a stray dog. He ends up adopting it and taking it home with him to be his ne partner. Yes, Robocop adopts a dog, and it’s wonderful.